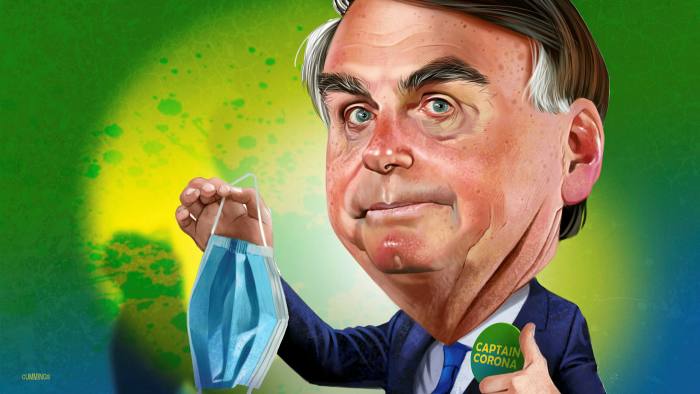

Brazil: COVID, chaos and a ‘Christian Majority’

Compartilho texto publicado em Oxford House Weekly Briefing, em 24/09/2021

https://www.oxfordhouseresearch.com/brazil-covid-chaos-and-a-christian-majority

Brazil: COVID, chaos and a ‘Christian Majority’

Brazil has been – and still is – one of the epicentres of the COVID pandemic. To-date, it has recorded 21.3m cases and 593,000+ deaths. Horrendous statistics. The true figure is probably much higher. Few families have been unaffected. Tough times, indeed, for me and my family here in Recife, as it has been for all of Brazil’s 230m citizens. We are, it sometimes feels, lost in the deep Amazonian darkness of Brazil’s COVID crisis and far from the light at the edge of the burning forest. Arguably far worse than the sad statistics and crippling socio-economic chaos COVID has caused, is the fact that Brazil belongs on a list of countries in which COVID has been politicised, if not cynically weaponised. What has happened in Brazil is not an ‘accident of nature’, it has become for the country’s leaders a politically useful ‘act of God’.

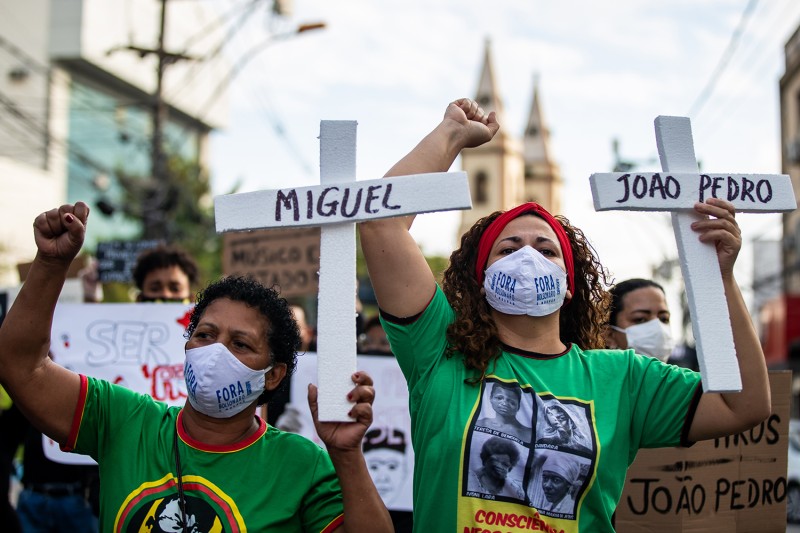

(AP Photo/Andre Penner)

Let me explain. The pandemic reflects a much larger socio-political and religious crisis in Brazil. Central to this has been the rejection by President Jair Bolsonaro (b. 1955; Pres. 1 January 2019 – present), and his ‘independent’ right-wing coalition, of everything ‘global’ and anything ‘left-wing’. So, ‘global’ is meddling in Brazil’s ‘national affairs’, ‘left-wing’ anything that offends the regime’s right-wing views on, say, (political) ‘corruption’ and (sexual) ‘depravity’, on the (low) status of ‘minority values’ for the ‘law-abiding’ Brazilian ‘majority’, or on the (illegitimate) expression of ‘environmental opposition’ to the government’s (exemplary) ‘development’ strategy. In the pandemic, WHO has been charged with ‘global’ meddling and ‘dictating’ Brazil’s ‘national’ health policies; while ‘left-wing’ has been used of everything from business closures to socio-economic strategies to help the unemployed, from those described cynically as ‘benefitting’ from labour deregulation and wage reduction, from zero-hour contracts and easy sacking. Seeds of the present crisis were sown years ago, but this is its bitter fruit today: help is a hindrance, values are inverted, policies to stimulate an ailing economy or protect nature and the health of its citizens, ridiculed. And this in a country that claims it has and is led by a ‘Christian Majority’.

(Creator: Joedson Alves, Credit: EPA)

Bolsonaro is not having it all his own way. COVID has created fissures in the regime. A recently established Parliamentary Inquiry by the National Congress has begun to reveal the prevalence – and catastrophic consequences – of ‘denialism’ (Port. negacionismo) at the highest level (including, little known, but powerful, political advisors). It is this conscious ‘denial’ of ‘global’ (sic) scientific evidence and a contrived pseudo-medical confidence in ‘natural means’ (viz. herd immunity) that led the Bolsonaro regime to give free rein to COVID-19 (aka like any other virus), and to consign half a million Brazilians to sickness and death, a majority in 2021.

Look at the statistics again: they make for dismal reading and are, by any standard, about more than a struggling health system or incompetent government. In the 55 days between 17 March and 10 May 2021, deaths ran at a weekly average of 2000+ per day, peaking at 3125 on 12 April. That weekly average didn’t fall below 1000 deaths until 1 August: today it is just under 900 per day. But – and this is crucial – from March 2019 onwards State Governors and Municipal Mayors reported harassment by government cronies for imposing health restrictions or urging a nationwide vaccination programme; and this, while the few regions that had vaccines were reporting lower rates of infection and death. Bolsonaro rejected the evidence: it represented for him unacceptable ‘global’ pressure and a ‘left-wing’ ideology. Members of his immediate family with government positions (N.B. his sons are a Senator, an MP, and a local councillor in Rio de Janeiro) joined then US President Trump in stoking the fires of opposition to the major source of Brazil’s vaccines (or their components), China. Roll on eighteen months. Six months into Brazil’s mass immunisation, 52.9% have received one jab only, 22.8 % two; and this in a public health system that has since the mid-1980s been lauded internationally for its sophisticated immunisation programmes. And let’s be clear, if COVID-19 per se was not a sufficient threat, popular perception has been battered by government disinformation, by politicised medical advice and fringe scientific opinion (and associated blogging) on the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, and by blatant disregard for common-sense and sanitary advice by the President and his supporters. Brazil’s public health is, it seems, at an all-time low, its socio-political antibodies deeply compromised.

Come back to the Parliamentary Inquiry. It has made some progress. Allegations of corruption have been directed against government representatives in the Ministry of Health, who have, it appears, added a $1 ‘fee’ to the $3.5 cost of every Astra Zeneca vaccine – all 400m doses! The contract was cancelled when these details came to light. President Bolsonaro has been indicted for failing to act swiftly – in Brazilian legal jargon, he is facing impeachment for ‘prevarication’ – when malfeasance was reported. Other allegations of corruption are gaining traction through document searches and the sworn evidence of officials, politicians, and businesspeople.

In other words, the federal administration is working; albeit, according to its own terms and justifications. But it must be stressed, good sense, sensitivity to human dignity, and respect for social and environmental (bio-)diversity during the pandemic have more often been stirred by internal and international pressure and embarrassing government defections than original policy decisions.

Religion is always a major factor in Brazilian politics. The role Conservative Evangelical and Pentecostal leaders have played in the COVID crisis has been both decisive and disappointing. Many have come out in support of the President and (equally controversially) claimed to speak for the ‘Christian Majority’ in the (generally conservative) Protestant communities of Brazil, despite grassroots survey evidence to the contrary. Through their un-masked public rallies and media appearances, Pentecostal and ‘Evangelical’ leaders have promoted open churches, disregarded public health warnings, endorsed anti-vaxxers, and urged prayer and fasting for the President and his party.

If you wonder why some Brazilian Christians have responded to COVID as they have, you need to be aware of two key theological principles they espouse. First, recent Brazilian Pentecostal leadership, like other conservative Christian groups, subscribes to versions of ‘dominion theology’; that is, confident belief in their divine right to shape national life. In turn, a distinct group of Reformed Presbyterian and conservative Baptist leaders in Brazil have adopted a (biblically literalist) ‘reconstructionist’ theology in which God’s law, inscribed in the whole Bible, is given to shape government and determine the sphere and limitation of human freedom, activity and morality.

To set present actions in an historical context. From the mid-1980s Pentecostalism has been on the rise in post-dictatorship Brazil and significantly impacted the character and agenda of the country’s public life and popular religiosity. The growth of Pentecostal churches led to early calls to redefine the national identity of historically Catholic Brazil, and to formally ‘include’ Protestants. 5% of Brazilians self-identified as Protestants in the early 1980s. The Census in 2000 saw that number jump to 22%, with some evidence suggesting 33% is now nearer the mark. Statistics show that most of this is growth comes from Catholic ‘conversions’ to Protestantism – or, more accurately, to charismatic, miracle focussed, prosperity preaching, Pentecostalism.

Over time, the call to restate Brazil’s national and religious identity and ‘Christianize’ the political order bore fruit. The inclusion and participation of Protestants at every level of Brazilian life and politics was encouraged. Self-confessed Protestants, led by Pentecostals, stood for the National Congress. In time, an Evangelical Caucus emerged in the Chamber of Deputies (Brazil’s lower house of representatives). Under the former Trade Union leader and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (b. 1945; Pres. 2003-2010), ‘Evangelicals’, as Pentecostal leaders chose to be called, extended their influence in government and society. As members of Lula da Silva’s successful 2002 election campaign, ‘Evangelicals’ were appointed Ministers, Senior Advisors, and top Administrators in what became a thirteen-year coalition government (re-elected 4x) formed around the socialist, now social democratic, Workers’ Party (founded in 1980).

To understand the interplay of faith and politics in Brazil, we need to drill down into history. In the 1986 congressional elections (which coincided with the calling of a Constituent Assembly that drafted and promulgated the new 1988 democratic Constitution), thirty-two Pentecostal and mainline Protestant representatives were elected out of 494. This set a trend which peaked years later when almost a fifth of the Federal Deputies in the five-hundred-member Congress were ‘Evangelicals’. Prior to 2003, the first year of Lula da Silva’s administration, the aims of the ‘Evangelicals’ were mostly limited to religious and moral issues, viz. they sought corporate benefits for local churches and denominational structures, and vetoed gender equality and sexual rights legislation and policies (i.e., abortion and same-sex relationships) to uphold ‘traditional family values’. ‘Dominion theology’ and ‘reconstructionism’ were both satisfied.

A groundswell of opinion sought the ‘inclusion’ of Brazil’s Protestant ‘minority’ in public life. From 2003, ‘Evangelicals’ gained greater access to power. Grass-roots achievement won them many friends; but their success bred competition and political tension. A new ‘Evangelical’ political elite emerged with legislators, senior managers, and leaders of vast new churches eager to engage (or own) the media and shape public opinion. US values and techniques were adopted. Dissenters – particularly Christian social activists and left-wing politicians – were challenged for supporting policies and programmes that empowered social minorities and enlarged the space for, and discourse around, pluralistic values, both political and personal.

(Photo APU GOMES/AFP/Getty Images)

Three other milestones on Brazil’s path to Bolsonaro and his regime’s response to COVID-19 can be identified.

First, the rise of public ‘Evangelicals’, the increasing congressional profile of three Protestant denominations (Assembly of God, by far the largest, Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, and Foursquare Gospel Church) and their combined influence on (among other parties) the Brazilian Republican Party and Social Christian Party, and disagreement over moral issues, led to a split with the Workers’ Party and projection of ‘Evangelicals’ into a decisive new role as political power brokers. Flexing their new political muscle, ‘Evangelical’ mandarins joined the parliamentary judiciary coup that ousted and impeached Lula da Silva’s successor Dilma Rousseff (b. 1947; Pres. 2011-2016) in 2016. The details of Rousseff’s impeachment are revealing. She was charged with ‘tinkering’ with the Federal budget to circumvent spending limits; nothing new here, nor hitherto adjudged criminal in the eyes of the Court of Accounts. Within days of Rousseff’s impeachment, Congressmen changed the law to allow for precisely the measures she had been accused of, and Evangelical leaders worked to unite conservative opposition (viz. Catholics, Spiritists, Jews and secularists) to form the new government. Brazil’s new right-wing agenda was germinating.

Second, the new right-wing ‘Evangelical’ lobby moved against Lula da Silva in 2018, when polls showed he had a fair chance of re-election. ‘Evangelical’ lawyers, public attorneys, politicians, and judges smelt blood. The former President was found guilty of corruption and embezzlement and imprisoned for over a year on grounds and a legal process now deemed unconscionable political ‘lawfare’ by Brazil’s own Supreme Court. In the political vacuum Lula’s side-lining conveniently created, the thrice married Jair Bolsonaro, expelled from the army for bombing a barracks to protest army pay (!), became President, his motto (again satisfying ‘dominionists’ and ‘reconstructionists’) the neo-Nazi tag ‘Brazil above everything, God above all’. In the wake of his election came (slightly fewer than expected) appointments of ‘Evangelicals’ as General Secretary of the Presidency, Ministers of Education, Family, Women and Human Rights, and Attorney General – and all in the name of Brazil’s ‘Christian Majority’. The former Minister of Justice and Attorney General, André Mendonça, a Presbyterian pastor and public prosecutor, has now been nominated by the President for the Supreme Court and is awaiting Senate approval. In April 2021 the legal action against Lula was declared illegitimate, his convictions and outstanding indictments quashed.

Third, Donald Trump’s election as 45th US President in January 2017 strengthened North-South links between ‘the American right’ and Bolsonaro’s ‘Christian Majority’. On 5 September 2021, the Financial Times reported Trump supporters working to ‘Make Brazil Great Again’. Brazil’s Conservative Christian public discourse has US ‘Christian right’ antecedents, viz.: Brazil faces an existential moral and religious crisis of unprecedented proportions; the threat of socialism and corruption justify repressive policies; dissent is unpatriotic. The ‘Christian Majority’ narrative in Brazil has united Pentecostals and mainstream Protestant ‘dominionists’ and ‘reconstructionists’ with their conservative Catholic, Jewish and Spiritist counterparts, and secular sympathisers on the political right. They claim to represent Brazil’s ‘Majority’ numerically and culturally. Opinion polls and Brazilian popular culture consistently challenge unhyphenated claims to this socio-political hegemony.

Two final points before I end, one negative, one positive.

First, disturbingly, the prime targets of much ‘Majority Christian’ animus are social, ethnic, and religious minorities, groups who have suffered much already on their journey to citizenship and acceptance. Like State Governors and Municipal Mayors who promoted social restrictions and vaccines to fight COVID-19, minorities face state-sanctioned violence and intimidation. They are interpreted as a threat to the (purportedly democratic) ‘Christian Majority’ on moral grounds. But threat they clearly are when they invoke Human Rights legislation in the Brazilian Constitution and protest marginalisation by a politically biased media. Meanwhile, a stream of policies and bills before the National Congress, with the support of ‘Evangelicals’, perpetuate antagonism, intimidation and the reversal of post-dictatorship Brazil’s democratization.

(Buda Mendes/Getty Images)

Lastly, and more positively, there are signs of a re-composition of critical voices in Brazil’s religious communities and society at large. Polls show a growing disconnect between ‘conservatives’ and the population as whole. Opposition parties and pro-democracy media have frustrated government-backed legislation. The Supreme Court and higher specialised courts (e.g., the Electoral Court) have woken up to their legal power and societal responsibilities, and, under intense pressure from Bolsonaro and his supporters, have launched inquiries into the President’s actions, including his alleged harassment of the Legislature and Judiciary, and financial corruption. Challenges to the convenient alignment of Brazilian Christianity with Bolsonaro’s political agenda, have also emerged recently from the Catholic Bishops’ Conference, from representatives of various Protestant denominations, and from countless Christian collectives. So, some light – just a little – on an otherwise tense and tortuous political scene here in Brazil, and, but for the hope of resurrection, a sense of dread that Christian credibility has suffered a mortal blow by its wilful co-option to, or mindless embrace of, thoroughly unworthy political machinations that have left hundreds of thousands dead in the COVID pandemic.

Professor Joanildo Burity, Associate

Comentários

Postar um comentário

Solicitamos que os comentários mantenham linguagem respeitosa e apropriada às postagens propostas. O conteúdo é livre, mas não serão permitidas postagens ofensivas.

We ask that comments stick to respectful and appropriate language. Ideas can be freely expressed, but offensive posts will not be allowed.